A guiding light through Nature’s darkness: symmetry in physics

In the last century, symmetries gained a central place in theoretical physicists’ understanding of the puzzle of reality.

An article by Mattia Cesaro

From phenomenological observations tied to beauty and perfection among early Greeks, the concept of symmetry has evolved in time and has been mathematically formalised, to such an extent that it represents today a fundamental guiding principle in the construction of modern physical theories. In this article, I will explore the notion of symmetry in physics, dive into the powerful connection linking symmetries to conservation laws, and remark on the importance of symmetries for our comprehension of nature.

Symmetries of physical laws

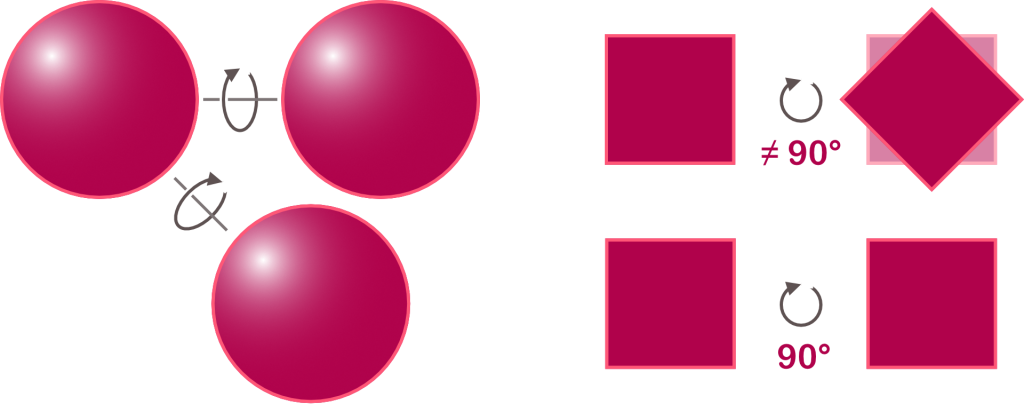

The concept of symmetry in physics is quite similar to the intuitive understanding we have of it from our everyday life. Take an object, apply an operation to it (e.g. move it, rotate it, etc.): if it does not change, we will then name the operation a symmetry of the object, and we will say that it leaves the object invariant. One of the typical examples is the rotational symmetry of a sphere: the sphere looks like itself by rotating it by any angular amount in space. Of course, a square also enjoys some symmetry: if we rotate it, but precisely by 90 degrees this time and not by any amount we want, it still looks like the same square, as if this rotation did not take place.

This situation can be made more general. In addition to the symmetries of concrete single objects, we are indeed often interested in those of entire systems and even of the physical laws themselves, because they condense patterns and regularities of the Universe which do not depend on the specific phenomenon we are studying. But what does it mean for a physical law to possess a symmetry? It means that there exists a set of operations that we can perform on the system under analysis, such that the physical laws (or rather their mathematical form) the system obeys, do not change. For example, we might wonder what could possibly happen to the outcome of an experiment if we carry it out in our laboratory here and now, or if we displace the very same laboratory by some meters in one direction (keeping all other conditions the same). Or if we look at the laboratory rotated to a different angle. If we perform the experiment today or tomorrow. The answer is nothing. Such transformations are called in order translations in space, rotations in space, and translations in time, and the physical laws governing such experiments are all left untouched by them; the transformations represent symmetries of the physical laws to which the system is subject.

Let us try to be more formal. Almost all the information (initial conditions are excluded) concerning the dynamics of the system, namely its evolution in time and the laws governing it, is quite elegantly encoded into a single mathematical object, called the Lagrangian. For simple systems like a mass in free fall, or a mass attached to a spring, the Lagrangian simply amounts to the difference between kinetic and potential energy of the system: for more complicated systems, it becomes a more elaborate gadget. We can apply all sorts of transformations to this object, and whenever the transformation we apply is a symmetry of the system, the Lagrangian stays the same. This statement is not entirely accurate, as, depending on the specific instance, the Lagrangian can also change by a (harmless, for what concerns the dynamics of the system) total derivative term. In the rest of the essay, let us nonetheless stick to the easiest possible case of an unchanged Lagrangian. This makes more precise the intuitive idea of the symmetry of a system given above.

Noether theorem and conservation laws

We are now in the position to discuss the deep connection between symmetries and conservation laws discovered by the German mathematician Emmy Noether in 1915. Conserved quantities are called this way because they do not change with time: they are the same at the beginning and at the end of a process, and are sometimes also called constants of motion. A very well-known example, proper to an isolated system (namely of a system with no exchanges with the surrounding environment), is the energy: along the process, the latter might change form, say from light to heat, but the total amount of energy in the system will not change. Conserved quantities happen to be extremely useful in determining the dynamics of a system in what would often be an otherwise very complicated analysis, but they are not always easy to find a priori. The remarkable result proved by Emmy Noether is the following:

Whenever the system enjoys a continuous symmetry, there exists a conserved quantity associated with, and proper to, each specific symmetry, that we can build explicitly.

Here, continuous intuitively means that the application of the transformation can be broken down to the application of a very large number of very tiny transformations: this is to be opposed to discrete symmetries, like a reflection, which instead cannot. For example, we can look again at the two familiar rotation symmetries of the sphere and of the square (Figure 1): only the sphere’s one is a continuous symmetry, whereas the square’s one is discrete, because if rotated by any arbitrary tiny amount, the square won’t look like itself anymore.

The theorem has had profound implications for the way we interpret the physics of the world that surrounds us. Let us look again at the laboratory experiments and at the symmetries of physical laws. Because the physics of the experiments is the same in two displaced laboratories, then by Noether’s theorem, linear momentum is conserved. This quantity is defined as the total amount of masses involved in the experiment times their respective velocities. This means, for example, that the way two billiard balls collide elastically (if we neglect friction) on the table can be understood as arising from the space invariance of the physical laws, by the theorem.

Because the physics is the same in the rotated laboratory, then by Noether’s theorem, angular momentum, the rotational analog of the linear one, is conserved. Therefore, angular momentum conservation, a famous example of which is the ice-skater spinning faster or slower around her rotation axis according to whether her arms are outstretched or withdrawn, can be seen to descend from the fact that the laws of physics do not depend on the angle from which we measure things.

Finally, because the physics is symmetric in time, namely, it is the same today and tomorrow, energy is conserved by Noether’s theorem. You can appreciate the depth of Noether’s result: the famous statement of conservation of energy in an isolated system, namely, that “nothing is created and nothing is destroyed, but everything transforms”, can be ultimately regarded as a consequence of the time invariance of the physical laws.

The fundamental role of symmetries in physics

We have here only touched upon the most basic examples of symmetries and conservation laws in nature. But it would be only a slight overstatement to say that high energy physics became the study itself of symmetries of nature. There happen to be many more symmetries of a less intuitive kind, which play a crucial role in modern physics. We proceed here to enumerate some of them, without any expectation of exhaustiveness or depth of explanation.

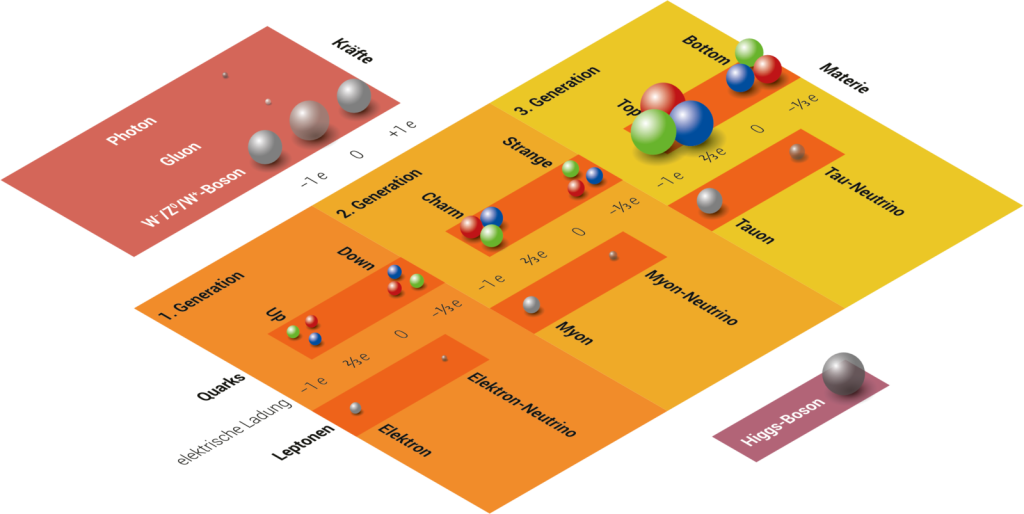

Gauge symmetries, for example, lie at the heart of some of the most successful theories ever devised, from electromagnetism to the Standard Model of particle physics. For the latter, the role played by symmetries is even more remarkable, as they literally told physicists where (for example, in which energy range) to look for new particles at the time yet to be discovered. And these particles were discovered precisely where symmetries were pointing at!

Inspired by these striking successes, researchers theorised more symmetries whose existence is yet to be proved, in order to explore their potential consequences on existing models. Supersymmetry, for example, should relate two different classes of elementary particles known as bosons and fermions. The light-particles named photons, for example, belong to the former class, while the latter class comprises the matter that surrounds us and that we are made of, like electrons and protons. Particles belonging to these two categories behave very differently (for example, bosons can be “squeezed” together in great numbers, contrary to fermions, which by the Pauli principle cannot); supersymmetry links these two families, predicting for each particle of one kind the existence of an additional, corresponding “partner” of the other kind (yet to be observed). Two prominent candidate theories for reconciling general relativity and quantum mechanics, namely String Theory and supergravity, feature supersymmetry as an indispensable ingredient in their formalism.

And what about Noether’s theorem? All of the aforementioned symmetries are no exception and carry their own conserved quantities according to the theorem, providing a good example of how general and pervasive the latter is in physics. These quantities are less intuitive to understand from alayperson’s perspective, but still very useful when performing computations. For instance, the conserved quantity associated with supersymmetry is something called supercharge, which is precisely the object that transforms bosons into fermions and vice versa.

Less conventional symmetries named dualities, on the other hand, do not abide by the theorem and do not carry associated conserved quantities: they are not symmetries of the Lagrangian, but they still leave untouched the dynamics of the system. In the context of String Theory, so-called U-dualities have been fundamental in connecting what were previously thought to be very different models into a single, more general and yet mysterious theory which transcends strings themselves, called M-theory. Another kind of duality is the conjectured one relating a gravitational theory to a quantum field theory without gravity, known as gauge-gravity duality: this constitutes a cutting-edge research topic. According to this hypothesis, our Universe could be equivalently well described by either a theory of quantum gravity or purely in terms of an associated, gravity-free, quantum field theory. Despite the absence of gravity, this quantum theory has to live in one spacetime dimension less than what we observe. In this context, symmetries become again fundamental, as they represent key aspects to be compared on both sides of the conjectured correspondence to test its validity.

As we have seen, the role played by symmetries and conserved quantities in the development of physical theories is a prominent one. If in less recent times symmetry was just regarded as a nice property of a physical system, the situation changed completely in modern physics, where it has been adopted as a fundamental feature in the crafting of realistic models describing how our Universe behaves. With time, it became clear that the importance of symmetries in physics is essential, their meaning a deep one, to the point that nowadays we hope they could provide a promising guiding principle towards a theory unifying all known fundamental interactions.

Further Information

Colophon

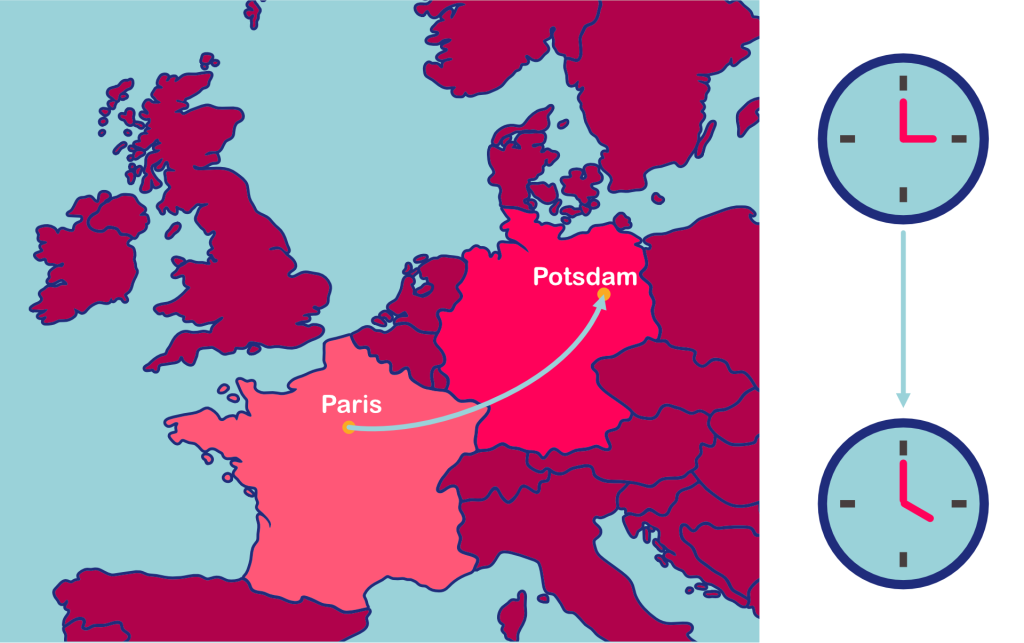

Mattia Cesaro works at the Albert-Einstein-Institute in Potsdam Golm

Citation

Cite this article as:

Mattia Cesaro, “A guiding light through Nature’s darkness: symmetry in physics” in: Einstein Online Band 16 (2025), 16-1003