The long journey to the center of our galaxy

A conversation with Reinhard Genzel about stars at the center of the Milky Way, the forest, and the Nobel Prize

An article by Jens Kube

Question: Prof. Genzel, looking at your scientific career, it seems like a major project spanning decades. How did your personal journey into astrophysics begin?

Reinhard Genzel: It all started in Bonn, in radio astronomy. It was an exciting time: interferometry was just becoming a crucial tool for visualizing structures in the universe with high resolution, and the first molecules were being discovered in interstellar space. My father, himself a physicist, instilled in me an early love of experimentation and analysis. And later, in Berkeley, I had the opportunity to work with Charles Townes, the pioneer of laser and maser physics. Working with him there was a dream come true for me. His approach to research had a profound influence on me: curious, persistent, and at the same time open to completely new avenues.

In the 1960s, quasars were discovered—extremely bright, compact objects. What significance did these mysterious objects have for your work?

Quasars were a revolution. We knew that they were far away and at the same time incredibly energetic. The only plausible explanation was a black hole with millions or billions of solar masses devouring matter. This process – known as accretion – releases enormous amounts of energy, mostly in the form of X-rays and radio waves. But at that time, it was only a model. The crucial point was that we had to learn how to measure masses. And we had to do it directly, not just via radiation.

How did you come up with the idea of studying the center of our own Milky Way?

In 1971, Lynden-Bell and Rees proposed the theory that a supermassive black hole could be located at the center of the Milky Way. It is the closest example of such an object—our local laboratory, so to speak. But we cannot see the center in optical light because dust lies between us and the galactic center like a thick curtain. Infrared was therefore the key, because its longer wavelengths penetrate the dust. And the question was: if there is a black hole there, can we directly observe its mass and its effects?

Your first evidence came from gas observations. Why didn’t that convince everyone?

Gas is a complicated fellow. It can be driven by all sorts of things: magnetic fields or stellar winds, for example. When we measured the gas rotation in the center, much of the evidence pointed to a mass of a few million solar masses. But the skeptics said, “Gas can be deceiving.” And they weren’t wrong. If you want to test gravitational physics, you need objects that move exclusively through gravity. Stars are ideal for this—but they were simply too faint for our telescopes at the time, and the Earth’s atmosphere was too disruptive for their observation.

So how did you manage to take the key step towards the stars?

Through technology and perseverance. We built better detectors, found the best telescope locations, and began to mathematically correct for the interference caused by the Earth’s atmosphere. The ESO has a truly fantastic site in Chile, and that’s where we were able to work. But it was a relatively small telescope, only 3.5 meters in diameter. What sounds commonplace today—adaptive optics, laser guide stars, interferometry—was completely new territory back then. Nowadays, we no longer use just one telescope, but all four of the ESO’s eight-meter telescopes. This gives us an incredibly good spatial resolution: more than a thousand times better than in our first attempts.

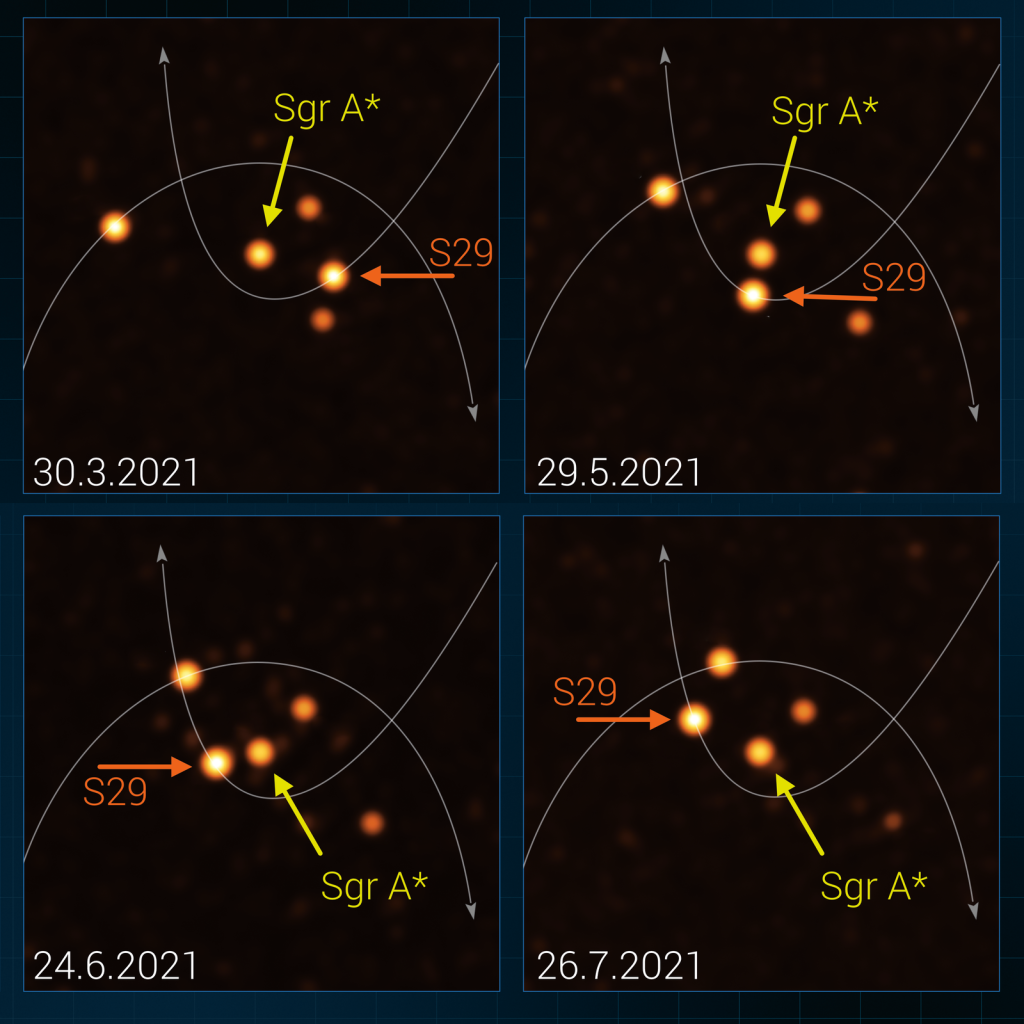

After a few years, we succeeded in detecting individual stars in the center of the Milky Way and tracking their movement over time—that is, over months and years. When we saw that some were moving at speeds of up to 1000 km/s, it was a key moment.

What did this finding mean?

Speeds of this magnitude and orbits that circle the center once every few decades leave little room for alternative explanations. A mass of four million solar masses concentrated in a volume smaller than our solar system. Stars cannot be accelerated magnetically; they only obey gravity. That was the first clear indication of a black hole.

And then you were no longer the only group working on it …

Yes, then Andrea Ghez’s group in California joined in. They had the advantage of having the large Keck telescope, which they used to confirm our findings within a few years. Two teams, two methods, two continents. And yet we came to the same conclusions. That made the results reliable. And it certainly helped the community to gradually accept that we were indeed dealing with a black hole.

Today, you even measure relativistic effects that follow directly from Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Can you explain that?

A black hole distorts space-time. Gravitational redshift, for example, means that light loses energy as it rises out of the gravitational field. This in turn causes the spectral lines of a star to shift to longer wavelengths when it is close to a black hole. Schwarzschild precession is the rotation of the star’s orbit – similar to Mercury in the solar system, only many times stronger. The stars do not describe recurring elliptical orbits; the position of the ellipse rotates slightly with each orbit. We have now measured these two effects. And we are working on using them to prove the spin of the black hole – that is, the rotation of the black hole that pulls space-time along with it. This would be a test of the so-called “no-hair theorem”: According to this theorem, a black hole is described only by its mass and angular momentum and nothing else.

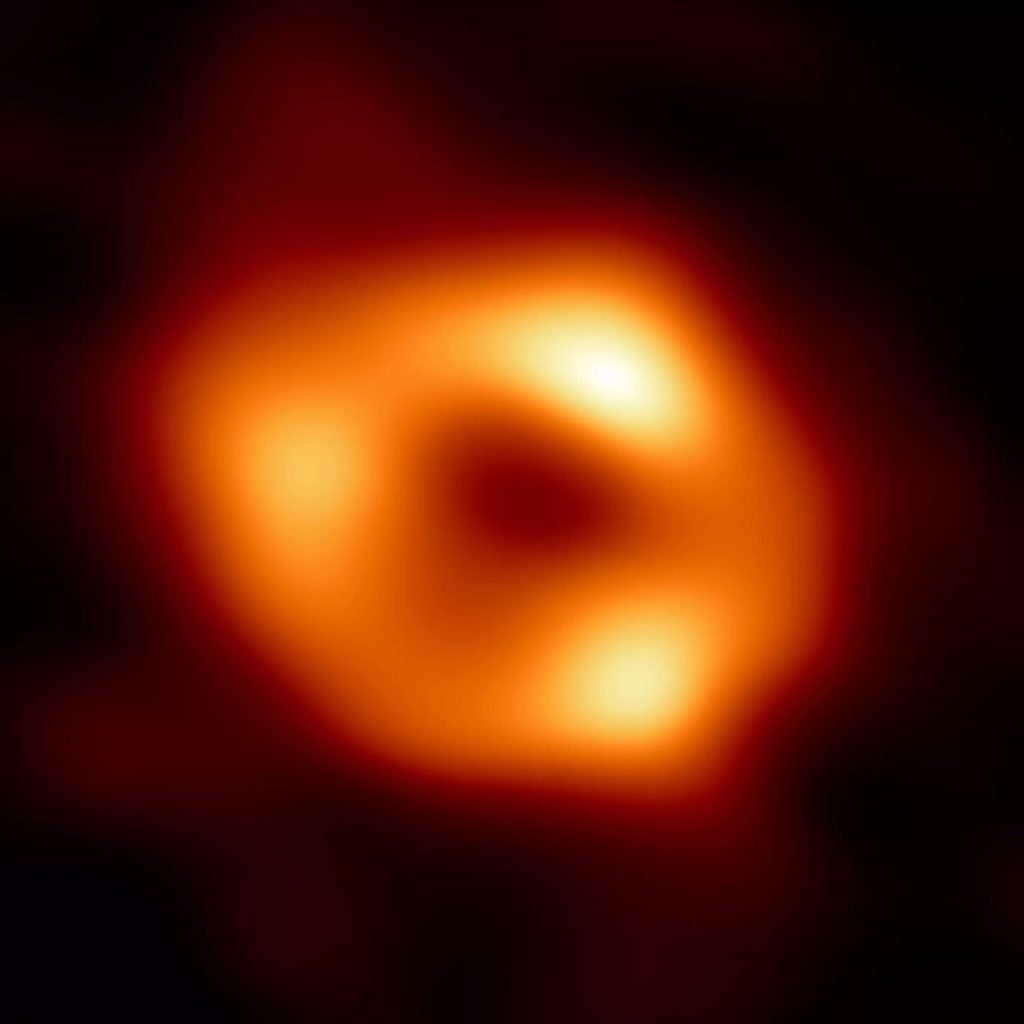

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) has provided an image of the “shadow” of the black hole. How do you put that into context?

The EHT measures radio radiation with a kind of Earth-sized telescope. When light passes the event horizon, it is strongly deflected. This creates a dark area—the shadow—whose size depends directly on the mass. And this size corresponds perfectly with our dynamic measurements. That is a wonderful confirmation. At the same time, the technology remains challenging.

Furthermore, the effects close to the event horizon cannot be seen very clearly because the plasma there is variable in a matter of seconds. It takes about ten to twenty seconds for it to orbit the black hole. Until now, however, the image has had to be averaged over an entire night. The image is, in a sense, a long exposure.

Let’s look to the future. LISA is a project to place a gravitational wave detector in space. Why is this so important?

Ground-based gravitational wave detectors can only observe the merger of small black holes – objects with ten to sixty solar masses. Supermassive black holes, such as the one at the center of the Milky Way, generate much lower-frequency gravitational waves. To measure these, detector lengths of millions of kilometers are required – and that is only possible in space. LISA could track a small black hole spiraling into a large one over a period of years. That would be a direct view into space-time near the event horizon – absolutely unique. To achieve this, it is important that all three planned LISA satellites are actually built and that politically motivated cuts by the Trump administration at NASA do not jeopardize the construction of the third satellite and thus the project.

Let’s move on to a personal moment: the Nobel Prize. Where were you when the call came from Stockholm?

We had known for over a decade that our work had been discussed repeatedly for the prize. Andrea Ghez and I had even received the Swedish Crafoord Prize in 2012 – a kind of antechamber to the Nobel Prize for fields that do not have their own Nobel Prize. Members of the Nobel Committee said to me on the sidelines of the award ceremony at the time: “If something important happens, we’ll take another look.” But I didn’t expect it. And when the call came in 2020, the hype was incredible. I was surprised – and very grateful.

How has the prize changed your perception of your own research?

Perhaps less than one might think. The Nobel Prize recognizes a result – but that result is the end of a very long journey. What matters to me is the collaboration within the group, the perseverance over decades, and the scientific curiosity. The prize is a gift, but the real joy comes from the research itself.

You mentioned your mentors who influenced your career. What advice would you give to young scientists today?

Firstly: find good mentors. People who give you freedom but still challenge you.

Secondly: have the courage to break new ground. Charles Townes once said to me: “If you’re exploring an unknown forest and suddenly hear a crackling sound behind you, it’s your colleagues following you. Then it’s time to enter a new forest.” That’s a wonderful image: science thrives on discovery, not administration.

And thirdly: patience. Research requires staying power. Some projects take years, some decades. If you learn early on to persevere, then at some point the moment will come when you actually understand something fundamentally new.

Prof. Genzel, thank you very much for the interview.

Further Information

Colophon

is a trained astrophysicist and a freelance science communicator. Since 2018, he is the editor for Einstein-online.

Citation

Cite this article as:

Jens Kube, “The long journey to the center of our galaxy” in: Einstein Online Band 16 (2025), 16-1002