Rotating Black Holes, Observations, and Working in General Relativity

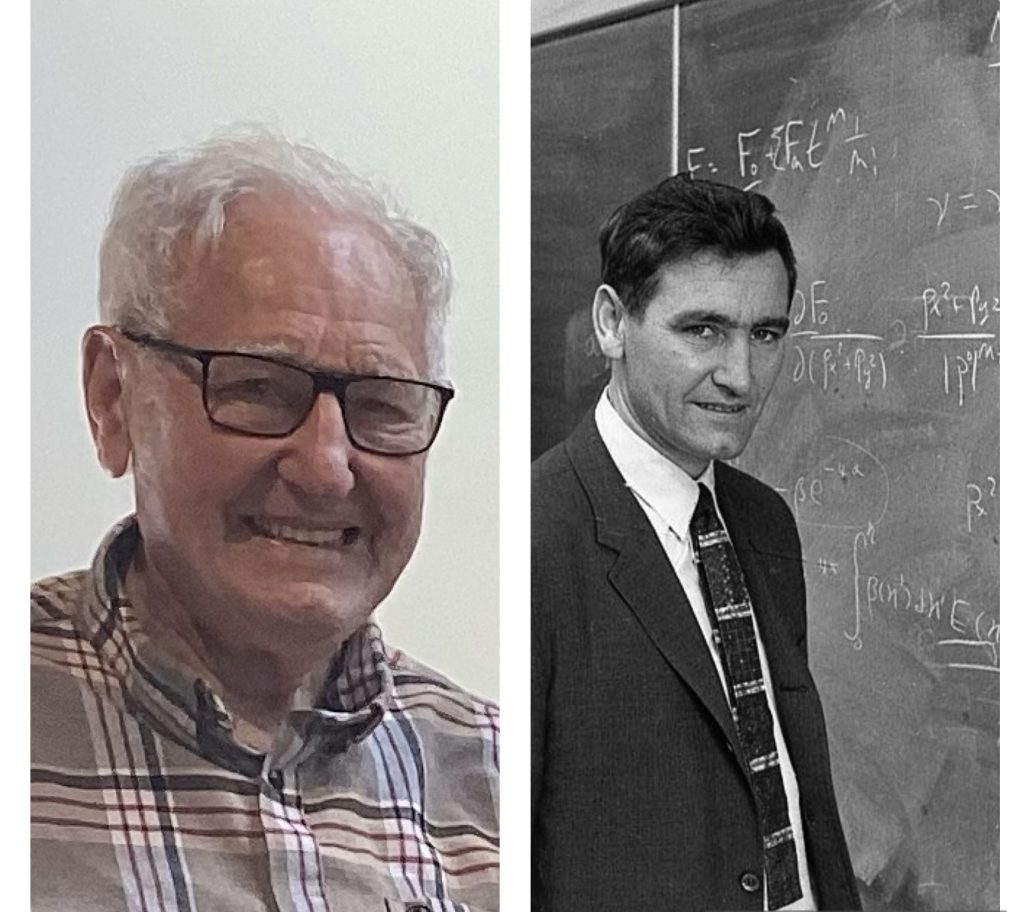

Roy Kerr worked on mathematical questions relating to general relativity theory in the 1960s. In 1963, he succeeded in describing rotating black holes in the “Kerr metric.”

An article by Roy Kerr (with Jens Kube)

When I am asked how I picture a black hole, I usually begin with its formation rather than with the formal structure of the equations. Consider a neutron star: an object of only a few solar masses, compressed into a very small volume. Its density is so high that gravity dominates all other interactions. If such a star accretes additional matter, it does not expand. Instead, under the right conditions, it becomes increasingly compact.

Within general relativity, this process can lead to the formation of an event horizon: a surface beyond which no signal can reach distant observers. The event horizon is not a physical membrane or a place where local physics breaks down. Early interpretations sometimes suggested violent or singular behavior at this surface, but these impressions were largely consequences of particular coordinate choices. When the spacetime geometry is described appropriately, the outer horizon is locally unremarkable. The essential feature is global: once inside, all future-directed paths remain inside.

This distinction between local experience and global structure is characteristic of general relativity and was often underappreciated in its early applications. Much confusion about black holes can be traced to a failure to keep these two aspects separate.

The necessity of rotation

Astrophysical objects rotate. Perfect absence of angular momentum is an idealization that is never realized in nature. Any realistic description of a collapsed object must therefore include rotation. For a long time, however, the only known black hole solution of Einstein’s equations was the non-rotating Schwarzschild solution.

By the end of the 1950s, this limitation had become increasingly evident. At the same time, astronomers were discovering extremely luminous sources at very large distances. These objects were initially misidentified as nearby stars, but it soon became clear that they were located in distant galaxies. Their luminosity implied an enormous energy output from a very compact region.

This combination of compactness and power strongly suggested that gravity played a central role. Yet without a rotating solution of Einstein’s equations, it was difficult to connect these observations to a coherent theoretical framework. Rotation was not a small correction; it was essential.

How the Kerr solution emerged

My own work did not begin with the explicit aim of describing black holes. I was studying a restricted class of solutions of Einstein’s field equations—solutions with particular algebraic properties that simplified the structure of the curvature. Around that time, mathematical techniques developed in the Soviet Union began to circulate more widely, although often without complete technical detail.

Several groups were working on similar problems. A widely used approach was the Newman–Penrose formalism, which rewrites the gravitational field in terms of many individually named components. I did not find this notation particularly helpful. With explicit indices, one can see immediately whether terms are consistent; algebraic mistakes tend to reveal themselves quickly.

While examining a preprint that claimed to solve the relevant equations completely, I noticed an inconsistency in a key relation. An expression that should have reduced to an identity did not do so. This indicated that the claimed general solution could not be correct.

I continued my own calculations, guided by a simple physical requirement: the solution should describe something localized at the center, and at large distances the gravitational field should fall off in a familiar way. I was not looking for the most general spacetime imaginable, but for one that could plausibly correspond to a real object.

When the analysis was completed, only one physically interesting solution remained. By studying its behavior far from the source, I could identify its mass and angular momentum. The presence of angular momentum showed that the solution described a rotating object. This solution, obtained in 1963, is what is now called the Kerr metric.

Initial reception and context

When I first presented this result, black holes were still viewed by many as mathematical abstractions. At a major meeting of relativists and astronomers, interest in my talk was limited. The focus was on newly discovered luminous sources, but few participants believed that exact solutions of Einstein’s equations would provide their explanation.

In retrospect, this reaction was understandable. At that time, general relativity had few direct observational anchors, and many relativists were primarily engaged with mathematical consistency rather than astrophysical application. The idea that an exact solution might describe a real object in the universe seemed implausible to many.

That view changed relatively quickly. As models of accretion and energy extraction developed, it became clear that rotating black holes offered a plausible explanation for enormous energy output from a small region of space. Within a few years, black holes became established objects of study in relativistic astrophysics, and the Kerr solution moved from a mathematical curiosity to a standard tool.

On being a mathematician or a physicist

I have often been asked whether I regard myself as a mathematician or as a theoretical physicist. The answer has usually depended on the audience. Among physicists, I was often described as a mathematician. Among mathematicians, I was treated as a physicist.

In practice, I consider myself an applied mathematician working on physical problems. My interest was always in physics, particularly gravitation. Mathematics was the necessary language, not the objective. I never aimed to prove theorems for their own sake, but to understand how gravitational fields behave.

Even now, when I look at new work, I find little appeal in calculations that are elaborate but disconnected from physical interpretation. Mathematics is indispensable, but only insofar as it clarifies the structure of nature. When it becomes an end in itself, it loses much of its value for physics.

Singularities and the limits of theorems

Over the years, I have been cautious about strong claims based on singularity theorems, particularly those associated with Roger Penrose and later extended by Stephen Hawking. My concern has never been with the ambition or originality of these works, but with their logical structure. Such theorems rely on assumptions—about energy conditions, global causality, or the behavior of quantum fields in curved spacetime—that are physically nontrivial. In subsequent discussions, these assumptions were often treated as if they were inevitable features of nature rather than hypotheses. Singularities appearing in exact vacuum solutions usually indicate the limits of an idealized description rather than the presence of a physically meaningful object. It is essential to distinguish clearly between what is proven, what is assumed, and what remains conjectural.

Observation as the final test

For me, the most convincing support for general relativity has always come from observation. An important early example was the binary pulsar discovered by Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor. The measured decay of the orbital period agreed closely with the energy loss predicted from gravitational radiation. This provided a strong and relatively clean test of general relativity in a regime far beyond the solar system.

The later detection of gravitational waves by LIGO was a major experimental achievement. Extracting such weak signals from substantial noise required extraordinary technical sophistication. At the same time, the interpretation of these signals depends on detailed modeling of the sources. This does not diminish the accomplishment, but it does define the limits of what can be inferred.

The images produced by the Event Horizon Telescope provided a different kind of confirmation. The observed ring-like structure surrounding a dark central region matched expectations for light propagation near a rotating black hole. After decades of abstract discussion, strong-field gravity had become directly visible.

Reflections and advice

If I were to offer advice to younger researchers, it would be to focus on problems with clear physical relevance. Mathematics is essential, but it should serve understanding rather than replace it.

Good supervision and a strong research environment can be helpful, not because authority guarantees correctness, but because experience can prevent avoidable errors. At the same time, independent judgment remains essential. Many useful results begin with someone taking the trouble to check a calculation that others have accepted without question.

Physics progresses through contact with observation. Theories may be elegant, and mathematics may be powerful, but it is ultimately nature that decides which ideas endure.

Further Information

Colophon

is a New Zealand mathematical physicist. Kerr taught for many years at the University of Texas at Austin and is considered one of the most influential figures in gravitational theory in the 20th century.

is a trained astrophysicist and a freelance science communicator. Since 2018, he is the editor for Einstein-online.

Citation

Cite this article as:

Roy Kerr (with Jens Kube), “Rotating Black Holes, Observations, and Working in General Relativity” in: Einstein Online Band 17 (2026), 17-1001